The Kukuri

In 1767 Prithwi Narayan Shah, King of the independent Kingdom of Gorkha to the west of Katmandu Valley invaded that valley and, despite facing numerically superior forces, succeeded in conquering them. Kathmandu fell on 29 September 1768 and thus he became the first King of Nepal.

When he invaded the valley, his troops encountered soldiers armed with traditional edged weapons such as swords, spears, and daggers. His own troops carried a comparatively new weapon; a short oddly curved knife and the inability of his enemies to develop a parry for this knife known as the KUKRI was, in some measure at least, responsible for their defeat. As long as edged weapons continued as the principal weapon of soldiers, the kukri remained superior in hand to hand conflict. Even today the kukri in the hands of an expert remains practically unparryable by sword, sabre or rapier.

The kukri, regarded as traditional to all hill tribes of Nepal, is both a formidable weapon and a tool that has innumerable uses from shaping timber to chopping up meat and vegetables. The blade is of tempered steel, slightly curved and exceedingly sharp. The handle is usually of wood or buffalo horn. A nick in the blade close to the handle serves the purpose of preventing blood from reaching the handle and is also symbolic of the Hindu Trinity of Bramah, Vishnu and Shiva. The blade is enclosed in a scabbard of wood and leather and the whole weapon is some sixteen to eighteen inches long.

Two small knives are found at the top of the scabbard, one blunt (Chakmak) and the other sharp (Karda). The correct use of the former is for starting a fire with a flint stone, and the latter is a skinning or general-purpose knife.

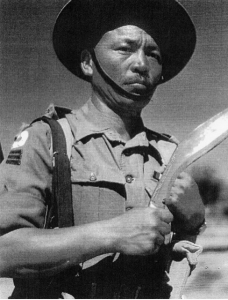

Most men and boys in the hills of Nepal possess a kukri and in the Service, every Gurkha soldier is provided with one from which he is never separated. The wrist action with which the kukri is wielded makes it extremely effective in the hands of one accustomed to using it.

For ceremonial and presentation purposes, kukris with scabbards ornamented in gold and silver and handles of ivory are often seen, and there is also a form of sacrificial kukri with a

longer blade and handle suitable for gripping with two hands. The latter is little used except for sacrificing animals at festival time.

The popular myth that blood must be shed every time a kukri is drawn from its scabbard is untrue and probably stems from the fact that if drawn in anger, then it is unlikely to be replaced without being used! Similarly, stories of the kukri being used as a throwing knife can be disbelieved.

Find out more about our history with the Gurkha Museum